Blog

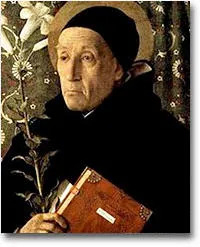

Meister Eckhart-Coming out to play!

Monday 7th July 2025

Mike Mullins

One of my heroes is Meister Eckhart (c.1260–c. 1328), the German Dominican mystic, theologian, and preacher. One of the first stories I heard about him was how one day he was deeply immersed in writing a theological treatise in the monastery scriptorium. Focused, disciplined, devoted. He was working out some complex idea about God, maybe on divine detachment or the birth of God in the soul.

Suddenly, a young boy from the village came into the room, barefoot and smiling, and tugged on Eckhart’s robe.

“Master Eckhart,” the boy said, “will you come out and play?”

The other monks were scandalised. How could a great theologian, a master of divine wisdom, stop such serious work for something so childish?

But Eckhart smiled, set down his pen, and replied:

“Yes, I will come out and play.” And he went out and played with the little boy.

That story deeply touched me because it told me that Eckhart’s spirituality was not a dry head based theology, of words and arcane concepts, it was a spirituality of mindfulness, presence, joy, and embodied experience.

Eckhart believed that overthinking or clinging to ideas about God could actually take you further from the divine. The child’s invitation pulls him out of intellectual striving and into the present—a sacred moment of joy and embodiment. The silence of play, of presence, of being with a child under the sky, is a kind of divine communion.

By stepping outside to play, Eckhart lives out his belief that God is not just in churches, books, or rituals—but in the simplicity of life, in a child’s laughter, in movement, in nature.

This echoes one of his most famous teachings:

“God is at home. It is we who have gone out for a walk.”

But in this story, it is Eckhart who returns home—not by thinking, but by playing.

In Christian mysticism, the child often symbolises the soul in its purest form: trusting, joyful, open, unburdened. Eckhart himself spoke of becoming like the child to receive the divine:

“Truly, God is nothing but play, and the only way to know God is to be in the play.”

Eckhart believed that the divine was not hidden away in churches, cathedrals or accessible only through religious services. Instead, he saw God in the very heart of nature—wild, still, and sacred. His insights on this are surprisingly fresh and practical, urging us to wake up to the divine presence around and within us.

Let’s explore Eckhart’s view on finding God in nature, weaving in his own words and moments from his life that bring his mystical vision down to earth.

"The eye with which I see God is the same eye with which God sees me."

This famous line by Eckhart reflects his belief in deep unity—the divine and human are not separate, and neither is nature apart from God. To him, the sacred wasn't only in churches or cathedrals—it pulsed in the trees, the stars, and even the quiet breeze. He wrote:

"Apprehend God in all things, for God is in all things. Every single creature is full of God and is a book about God."

This isn’t poetic fluff—it’s a call to attention. For Eckhart, nature reveals God, if we slow down enough to notice. That wildflower, that mountain stream, that still forest—they’re not just beautiful. They’re an aspect of the divine.

Living Simply, Seeing Deeply

Eckhart lived during a time when the Church was powerful, structured, and filled with rules. But his own life was marked by simplicity. He walked with peasants, preached in the vernacular (German instead of Latin), and spoke plainly. He once said:

"God is not found in the soul by adding anything, but by a process of subtraction."

He encouraged people to strip away distractions and noise—internally and externally. Imagine Meister Eckhart walking through a field in the Rhineland countryside, pausing at a stream, hearing nothing but birdsong and wind, and feeling that in this silence, God speaks. Not with words, but with presence.

The Stillness That Speaks

One of Eckhart’s favourite themes was Gelassenheit, often translated as "letting-go-ness" or surrender. It’s the peaceful acceptance of what is, and the quiet attentiveness to the now.

He said:

"Nothing in all creation is so like God as stillness."

Here, the forest becomes a chapel, the mountain a sermon. Nature doesn’t strive or shout. It is. That’s what Eckhart saw as holy. In his view, when we sit quietly beneath a tree or walk through a meadow with an open heart, we’re not escaping life—we’re stepping right into the heart of it. Into God.

A Story of the Cowherd

Though little biographical detail remains about Eckhart’s day-to-day life, one story (whether legend or fact) captures his spirit. A young monk once asked him how to find God.

Eckhart pointed to a cowherd watching over his cattle in silence at the edge of the forest.

“There,” he said. “He finds God in the same way I do—in the stillness, in the tending.”

This reflects a radical notion for his time: you didn’t need a monastery to be holy. You could be a cowherd, a farmer, a carpenter—and if you were present, open, and still, you were in the heart of God.

Becoming One with Nature

For Eckhart, union with God meant union with everything. Not absorption or erasure, but awareness. He wrote:

“The soul that is united with God is as wide as the whole world. The whole world is too small to contain God, but God can dwell in a single soul.”

What’s remarkable here is that this isn’t abstract theology. It’s profoundly experiential. Go into a forest. Feel your breath slow. Sense the stillness. That’s not like God. That is God, according to Eckhart. And you, breathing in that stillness, are not separate from it.

Sacred Simplicity

Meister Eckhart’s path wasn’t about escape—it was about awakening. He didn’t ask people to flee the world but to wake up to it. To see God not just in prayer, but in rivers, stars, animals, silence, and soil.

His message, in the end, is simple and accessible:

“If the only prayer you ever say in your entire life is thank you, it will be enough.”

And what better place to pray this than in nature—where everything, silently, is already saying it?